Read our perspective on what excites, motivates and moves us

It’s all about giving you access to the content that can spark an idea, challenge the way you think and grow your understanding of the world around you.

It’s all free and we’d love you to be part of the ever growing community of readers.

Hi, it's Tom here.

SXSW this year was different.

No scrambling from ballroom, to patio, to panel, to event and back to ballroom with a buzzword addled brain.

No, this year we did something altogether more rewarding. One location, three days and the world’s best marketers in the room. Brand Innovators @ Lamberts.

Maybe it was the Bloody Marys for breakfast, but the tone and tenor of the conversations I watched felt different too: less clout chasing, shiny-new thing praising and more focus on the power of the fundamentals of brand building. Recognising that there are no short cuts to becoming an iconic brand, but it takes more bravery, risk and creative practices to get there and stay there in the modern marketplace.

Here are some moments of timeless wisdom alongside some timely advice that I heard along the way.

You build the mythology, they tell the stories

“Nothing that you do will work as hard for you as the advocacy of a third party”

One emergent theme was that calling brand marketers the storytellers isn’t really accurate in the modern age. We are now world builders, the definers of the spirit and soul of the brand, but it is the people who love us that hold the power of telling our story through their lens.

That means we have to cede some control of the narrative and be more flexible with where and how we believe our brands can show up in the world.

To me, this suggests that we need new frameworks that break the rigidity of the brand key / brand onion…’ and instead create a strategy that operates more as a compass - a directional, ever-evolving reference point which defines our universe, but doesn’t micro-manage the journey.

Partnership is the new leadership

“No brand is an island anymore”

That partnerships are an absolutely critical piece of the marketing puzzle has never been more obvious. When everyone has seen everything, unexpected creative connections are one of our only remaining ways to jolt consumers out of their ‘seen it’ slumber.

El Pollo Loco at HypeBeast golf - sure, why not?

But getting these right isn’t just a matter of picking up the phone. The real challenge is to identify the strategy to build the right partnership to open up new audiences and tell new stories, and the creativity to execute them in ways that surprise and shine.

Boredom is the enemy, personal is the answer

We are all in the business of interrupting people”

Whether it’s B2B or bleeding edge nutrition, there is simply no room to be boring anymore. Playing it safe is in fact the biggest risk you take. As one marketer put it, “you have to take more swings and try more things”. You have to trust your emotional gut to create more emotional connections. I particularly loved how more than a few brands were building more meaningful emotional connections by showing up in local communities, meeting consumers where they’re at, and providing value versus selling it.

Again, this is a space that needs strategy. How are you constantly creating and delivering new and interesting, of the moment messages in context and being a part of the right cultural conversations?

Much food for thought. Thanks Brand Innovators, and to all of the fantastic speakers.

And if you are interested in hearing about our ‘Culture Compass’ product, which is built to deliver on the challenges above, please get in touch! enquiry@beentheredonethat.co

Tom Donohue,

Strategy Director at BeenThereDoneThat

Hi, it's Hollie here.

The creative industry idolizes youth like it’s the secret ingredient to creativity.

Actually, scratch that.

The WHOLE WORLD idolizes youth.

Lately, I've been thinking about how obsessed we are with staying young. I just watched The Substance with Demi Moore. Have you seen it?

Give me an activator to get my 21-year-old body back, and I’d pay a fortune for it. But like all these promises of youth, it comes with a cost.

So, instead of chasing youth, I’d rather celebrate what comes with age.

History proves that creativity isn’t confined to youth. Some of the greatest creative minds did their best work well into their 50s, 60s, and beyond — Matisse reinventing art with his cut-outs in his late 60s, Frank Lloyd Wright designing the Guggenheim at 91, Maya Angelou publishing poetry into her 80s.

Yet in advertising, if you’re over 40, you start to feel like milk edging towards its expiration date.

Out of date and out of touch.

So, when does that creeping sensation start?

The one where you feel yourself fermenting, curdling, sitting on the shelf with a giant ‘Reduced to Clear’ sticker slapped on your forehead?

Well, I can tell you, I’m nearing 40, and even typing that feels like an out-of-body experience. Like those numbers belong to someone else.

Not me. Surely not me.

I feel the fear creeping in, the same fear I’ve watched so many older creatives I know wrestle with.

Because to be honest, have you ever seen a woman over 50 in your creative department who wasn’t an ECD or CCO?

No? I didn’t think so.

I once (yes, once) worked with an incredible woman, a non-c-suite creative who defied the odds.

Until doomsday came.

Not actual death. Just another round of layoffs.

She, like so many others, was quietly phased out. Left to navigate the abyss of freelance.

How Do We Flip the Script?

What if, instead of treating age and experience like a liability, we could get people to see it as a creative superpower?

There’s a tired narrative that younger creatives are here to replace us. That’s nonsense.

The best work comes from intergenerational teams, but we need the chance to prove it.

So here come the stats…

The Data is Clear

- Age-diverse teams outperform homogeneous ones.

- A Harvard Business Review study found that companies with mixed-age leadership teams generate better financial returns and more innovative ideas.

- Investor's Business Daily found that older adults often excel in making connections between diverse concepts and synthesizing ideas, leveraging their extensive experience to drive innovation.

Why? Because experience and fresh perspectives fuel each other.

I genuinely love learning from young creatives. I absorb their energy, ideas, and new ways of thinking.

And I know that the speed and efficiency of being older isn’t at odds with them — it complements them.

The truth is that the lack of over 40s in the creative department is that most creatives don’t leave full-time jobs by choice. They get nudged out.

Enter your golden era.

One day, you’re a celebrated creative. Next, you’re a LinkedIn post about exploring "exciting new opportunities."

And here’s the thing: freelance at 40+ isn’t exile, it can be power.

Because the good news is, it turns out that clients are loving it. A 2023 survey by Upwork found that 36% of creative freelancers are over 40, and that number is rising.

Why?

Well, clients want experienced problem solvers who can skip the bureaucracy and get things done. The industry’s age bias is fueling a golden era of freelance and independent agencies, one where older creatives hold the power.

If we genuinely value creativity, we need to back it up with action. That means hiring, promoting, and retaining older creatives, not just applauding them after they’ve been forced out.

But What Can We Do Now?

✅ We can challenge the industry’s ageism.

✅ Continue to highlight the power of intergenerational teams.

✅ Demand that agencies treat long-serving creatives with the respect they deserve.

✅ Reframe freelance at 40+ as a strategic career move — not a fallback.

Cannes might hand you a lifetime achievement award if you’re lucky.

But your agency will quietly phase you out before you turn 50.

Creativity doesn’t expire.

But the industry’s outdated attitudes?

They went sour while we were all busy freelancing.

Hollie Fraser,

Freelance Creative Director, Talent Curator + Connector at We Are Shelance, Freelance Mentor

Further reading:

The Substance official Trailer

Statistics show that diverse teams outperform homogeneous teams

Top Innovators Are Never Too Old To Push The Envelope

Welcome to BeenThereDoneThat - Built Different. A series where we explore how industry leaders are challenging conventional wisdom and thinking differently to overcome their latest, greatest challenges.

In each episode of the series we pose three questions to our guests:

- What’s the biggest current challenge that’s forcing you to think differently?

- What’s the biggest aha moment or fresh wisdom you’ve picked up on that journey to date?

- What has been the single most effective practical step you’ve taken so far?

Hi, it's Saul here.

What is the biggest threat or opportunity for business right now?

My hunch is that outside geo-political challenges, the majority of people asked are going to say something involving AI.

Seeing technology as the main disruptive force is not a new thing, even before the arrival of ChatGPT and its like, the world of business was already obsessed with ‘disruptive innovation’.

Technology, we are told, presents the ultimate challenge for existing companies trying to stay in the game, or, the greatest weapon for founders seeking to change the way the game is played.

Technology is only as disruptive as the beliefs that shape it

This blinds us to the truth: The really disruptive businesses often use new technology, but they will always use unconventional beliefs and thinking.

If you look at the poster children of disruptive innovation, Uber and Airbnb: their technology wasn’t particularly new or disruptive, it was already being used in different ways and in different places long before they integrated it. This is true of their payment systems, in how they delivered peer to peer reviews and ratings, their tracking capabilities and beyond.

The technology was critical, it inspired new thinking, but it was their ability to question fundamental assumptions that enabled them to see what others couldn’t, so they could attempt to create value that others had not.

It was their maverick beliefs that created a potential new theory of value that they could then interrogate and try and deliver on, often through technology, not the other way around.

It was Airbnb’s ability to see latent room capacity in every home and every home owner that transformed where we stay when we are away from home. It was Uber’s ability to see a potential taxi in every driver and every car that revolutionised point to point travel.

The real problem: chronic strategic blindness

It is here we find the biggest problem for long term business success: strategic blind spots.

The most pervasive one seems to be what O’Reilly & Tushman call the ‘Success Syndrome’.

This is where the higher performing an organisation is, the stronger the systems to keep them doing what has made them successful in the past are: The KPI’s, the reward systems, the culture, is all designed to exploit what they are currently good at.

What that means is that their way of being is grounded in conventional wisdom. This makes it harder for them to explore what they might need to do to make money differently in the future. They are often very innovative but in an incremental way, in smaller optimisations of the dominant design of an industry. Not the kind of radical leaps that can disrupt that dominant design and catch them off guard (Hotels and Airbnb, Taxi companies and Uber).

Or, they do make radical leaps but then aren’t able to effectively commercialise it. Because the rest of the business is built for the old way of doing things, they can’t see how it fits with who and what they currently are: ask Kodak who invented digital photography, but then the likes of Sony Cybershot owned the new category, not them.

A new theory of value: The ability to see value others can’t, by thinking what others don’t

So how can companies consistently think differently, and how can they then integrate the new beliefs that emerge into what currently exists?

I use an approach inspired by Professor Todd Zenger’s brilliant ‘Theory of your firm’ thinking, then shaped by my own Oxford work and experiences working with companies large and small all over the world.

You need 5 ‘Sights’ and Convictions:

It first asks what the Job To Be Done is: What is the customer trying to do, independent of any solution.

Hindsight: What are the conventional thinking and beliefs that define current solutions? What do most people believe?

Foresight: What new theories of value can we see that others haven’t? What are credible alternative beliefs? (This is not easy; it requires looking for ‘Workarounds’ and going back to First principles: more on this in the ‘Maverick Model’ link below).

Insight: What capabilities do we have inside that can uniquely deliver on this new theory of value?

Out-sight: What additional capabilities, currently outside, might need to be in place in the future?

Oversight: How does this all fit together into a cohesive whole? How do we organise ourselves?

Each of these sights flows to the next so that they form a coherent new value driving theory. One that is powerful in the day to day, but also able to evolve to match the changing world around it.

Convictions: how to capture what the company believes is the way the category, industry, discipline can be with its new approach. It must light the fire (people find motivating) and also light the way (people know what to do).

Sense-Shape-Seize: Lastly, these Sights and Convictions are always in beta, are willing and able to - Sense: changes in the environment, in technology, in culture, in customer needs and competition. Then Shape: a response to that change. Then Seize: on that challenge or opportunity in a timely manner (before someone else does it for them).

It is why the whole system, and especially the Convictions, are held firmly in the moment but loosely over time.

Saul Betmead de Chasteigner,

Strategy & Innovation Consultant, Executive Coach and Associate Fellow at Said Business School, University of Oxford.

Further reading:

Strategy Masters Series: Maverick Innovation Model

Lessons from Oxford: The shape of a winning business strategy.

Argumentation, the engine of innovation and growth.

What Is the Theory of Your Firm?

Hi, it's Teigan here.

What do Oprah Winfrey, Rebel Wilson, James Corden, Elon Musk, Sharon Osbourne and rapper Fat Joe have in common? Besides being famous, they’re just a handful of celebrities that have admitted to taking Ozempic - the infamous weight loss drug now synonymous with a growing class of GLP-1 medications, including Saxenda, Victoza, Wegovy, and Trulicity, with more racing to enter the market.

Introduced in 2005 to help treat diabetes, by 2023, over 30% of new GLP-1 users in the U.S. were purely for weight-loss or preventative use. And while users are still disproportionately in higher income American households, earning on average $150k or more, these drugs are no longer just for the rich and famous. About 7 million Americans are currently taking these medications, and that number could hit 24 million by 2035, according to Morgan Stanley.

Growing up in Seattle, I felt privileged to have access to healthy food, yet I can’t remember a time where managing my weight wasn’t something in the back (or front!) of my mind. Clearly, I’m not alone. So, it begs the question…how did we get here? And what are the implications of how and what we eat in the future?

Ultraprocessed food and the effects of GLP-1 drugs

Since the 1980s, obesity in the US has soared, with three-quarters of Americans now classified as either overweight or obese. While previous hypotheses pointed the finger at overeating, energy intake and energy available have remained steady since 2000:

(National Library of Medicine)

Scientists, politicians and consumers are now pointing the finger at one thing - ultraprocessed food. A simple explanation of this category is “anything edible you can’t make in your own kitchen if you tried”. (The Daily, A Turning Point for Ultraprocessed Foods)

By the 1980s, 60% of the food supply in America was classified as ultraprocessed, and now it is estimated at over 70%. There are a couple of major reasons why ultraprocessed food is being attributed to rapid weight gain:

- When we eat minimally or unprocessed food, our gut bacteria consume around 22% of the energy through the digestion process, whereas with ultraprocess food, our bodies soak up 100% of the calories.

- Our brains are also wired to crave this type of food. Addiction scientists have coined the term “hyperpalatable” - food that has a high level of at least two nutrients (e.g. high in salt and fat, fat and sugar, etc.) which doesn't normally occur in nature.

So, why does this matter with the intake of GLP-1 drugs?

We’re seeing that it’s not just people eating less, but eating differently. GLP-1 receptors are found in the hypothalamus, which is the area that signals fullness. But perhaps more interesting, they’re also found in our reptilian desire circuitry, involved in addictive behaviors that trigger our brain’s dopamine reward system.

By helping regulate the release of dopamine, many people taking drugs like Ozempic are sharing a loss of interest in ultraprocessed food, reporting an unpleasant taste and mouthfeel. Instead, they’re opting for fresh produce and yogurt. As one user said, “I just started to realize strawberries taste wonderful by themselves.”

With 7% of America currently on Ozempic and intake accelerating across the UK and Europe (most notably Denmark, home of Novo Nordisk), this may have some companies rejoicing, and others wondering…what comes next? With some forecasts predicting up to 10% of Americans could be on Ozempic by 2030 and intake accelerating across the UK and Europe (most notably Denmark, home of Novo Nordisk), this may have some companies rejoicing, and others wondering…what comes next?

An opportunity for innovation

As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention, and perhaps this will be the push needed to fuel the next wave of breakthrough innovation in food & drink.

According to Mintel’s report on “The Role of Innovation in the Future of CPG,” the first half of 2024 had the lowest proportion of innovation since it began tracking new products in 1996. Within this, innovation within food and beverage has declined the most:

Coupled with steady price increases, big brands are continuing to face growing competition through private-label and challenger brands as the innovation cycle accelerates through AI.

“The rise of AI means bigger CPG brands are now operating in a ‘real-time world’. Innovation cycles that previously took years can now take just months, and algorithms can make sense of a dizzying array of new digital data points as they happen. As a result, bigger brands need to become more agile and faster to win the race for ‘white space’.” (Mintel, The Role of Innovation in the Future of the CPG Industry)

As these medications challenge our relationship with ultraprocessed foods, it opens the door for big brands to ride the tailwinds of these cultural shifts and emerging technology into new spaces, e.g.:

- Updated flavor profiles to adapt to new palettes

- Smaller portions to cater to diminishing meal size

- Enriched snacks to ensure sufficient intake of key vitamins and minerals

- Expanding into fresh food

We’re still at the early stages of understand long-term implications of how GLP-1 will impact our shopping and dietary needs, but for food and beverage companies, it could be an opportunity to reshape the future of the industry. I’m excited to see (and taste) what comes next.

Interested in learning more about our culture-first approach to innovation? Please reach out to enquiry@beentheredonethat.co.

Teigan Henry

Director at BeenThereDoneThat

Further reading:

Ozempic Could Crush the Junk Food Industry. But It Is Fighting Back.

A turning point for Ultra processed foods

Perspective: Obesity—an unexplained epidemic

The Role of Innovation in the Future of the CPG Industry

Hi, it's Dan here.

(Please note! This article is not designed to be ideological. The intention is to try and capture the sense of a changing dynamic, and discuss what this means for brands going forward).

Reshaping the political and cultural landscape

Mr. Trump has been back in the White House for about a month. I think most could agree that his administration is rapidly reshaping the political landscape, in ways that extend far beyond Washington.

The argument here is that Trump’s return to prominence as the driving force of American Conservatism signals more than just a shift in rhetoric and policy.

Amplified massively by social media, MAGA is also driving a cultural reset, in which nationalism, traditionalism and economic populism extend beyond the realm of political positions, to become a part of consumers’ identities. This means that the playbook is changing, not just for politicians, but for the media, and any institution that engages the public. And brands too.

This is already a market reality for companies whose products no longer seem to operate in a neutral space. The political, cultural, and economic divides in America—and beyond—will force brands to rethink who they serve, how they communicate, and what they stand for.

The merging of brand and political values

Trump's brand of leadership embraces conflict: the language is often “Us vs. Them”. Globalists versus nationalists, elites versus working people, liberals versus traditionalists. This plays well in the ‘attention economy’ where increasingly brands are being pulled into this polarisation - whether they like it or not.

We’ve already seen recent manifestations of this. Bud Light’s short-lived partnership with a transgender influencer led to conservatives launching a nationwide boycott. Target faced similar backlash over its Pride collection. Oatly is too ‘woke’ a brand for some. Meanwhile, companies like Chick-fil-A and Goya Foods have benefited from leaning in to conservative values. The MyPillow founder has a regular slot on Steve Bannon’s War Room!

I’m sure consumers will continue to choose products and brands based on price, quality, features and so on. But attributes have always played a role too, and ideology or political-leaning is increasingly going to be a part of brand image and hence consumer decision making.

What Trump 2.0 means for brands

With the Trump Administration influencing the cultural conversation globally, brands will need to navigate a shifting landscape. Here’s four things I can imagine over the next few years:

- Polarisation as the default setting

The idea that brands can “stay neutral” is fading. Whether it’s social issues, corporate responsibility, or even platform choices (think X under Elon Musk), companies need to accept that most decisions can and will be politicised. The question is not whether to engage, but how to manage the fallout when you do. Joining Blue Sky for example will be seen as a brand action.

- DEI and ESG Reckoning

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) and Environmental, Social, & Governance (ESG) initiatives are (very publicly) under pressure. Republican-led states are pushing anti-ESG policies, while conservatives are rallying against companies seen as too “woke.” Companies that built their brand identity around progressive values will need to decide: double down, adapt, or step back? The wrong move could alienate stakeholders, or worse, the Federal Government! We can see which way Zuckerberg has gone already. How will an activist brand like Ben & Jerry’s respond? And it’s not just the US. In the UK, for example, BP is publicly rowing back from the Green Transition (‘It’s And, not Or”)! Less equivocal than ‘Drill Baby, Drill’...but still a shift to the Right.

- Brands acting more like media companies

Elon Musk has demonstrated that direct, unfiltered communication is a hugely powerful tool in shaping public perception. Legacy media (and traditional advertising) no longer controls the narrative. Social media, influencers, and brand-led content dominate mindshare. To cut through brands will increasingly seek to act more like media companies, controlling their message rather than relying on outside platforms to do it for them. Brands who understand how to win will increasingly seek to own or dominate their own channels. (Examples here are brands aligning very effectively to podcasts with a good strategic fit, or the way Liquid Death has generated huge noise around their viral, sharable content ).

- More emphasis on consumer nationalism

“America First” economic policies are back, and that means expectations around domestic manufacturing, supply chains and corporate loyalty will change. Brands that lean into American identity—whether through sourcing, messaging, or direct alignment with populist values—may find themselves rewarded by conservative consumers. But brands that are seen as “outsourcing” jobs will be targets for scrutiny. If Trump’s tariffs materialise then this will become a global issue: maybe even Made in Britain will make a comeback!

How should brands respond?

The challenge for brands in the Trump 2.0 era is going to be about understanding how consumers (in the US and globally) are internalising the populist / conservative world-view. Brands need to make strategic decisions about where to engage and where to stay quiet.

- If a brand has built its reputation on progressive values, it needs to be ready for pushback, and to have a clear strategy to deal with it

- If a brand wants to be neutral, it must tread carefully, avoiding knee-jerk responses to cultural moments that may alienate

- If a brand chooses to align with conservative values, it should do so authentically: consumers can spot opportunism a mile off

To close, maybe we can say that Trump 2.0 feels like something more than politics as usual. If so, then it’s a cultural shift that we can’t ignore. Brands need to think about what they now stand for, and be strategic and intentional about how and where they engage as they navigate the new normal.

Dan Read

Doer of innovation

Further reading:

Divided We Shop: How the Brands We Buy Reflect Our Political Preferences

Leading with Corporate Purpose amidst DEI and ESG Backlash

2024 Edelman Trust Barometer - Special Report: Brand and Politics – Edelman

How CEOs Can Navigate a Polarized World

Hi, it's Ben here.

Is death inevitable? Some scientists are challenging the conventional wisdom that death is the only certainty in life. And some Silicon Valley types are throwing serious cash at the problem.

But, as with almost everything, it’s a case of defining the problem properly. We might not all want to live forever. But the emerging field of longevity science is uncovering insights that can help us all live longer and, crucially, live more enjoyably, especially in our latter decades.

And hey – it’s February. If we’re going to talk about death, we might as well do it during the season sponsored by doom and gloom. So here’s the question for today: how much control do we actually have over when we kick the bucket?

Netflix’s Don’t Die elaborates the more extreme end of longevity science. Bryan Johnson gets up at 4:30am, takes over 100 pills a day, eats mostly brussel sprouts and is so healthy that images of his rectum have gone viral.

If this doesn’t appeal, Dr. Peter Attia might have some more applicable advice for you. If you’ll allow me to summarise his entire work into a single word, it’s exercise. Nothing can improve your life expectancy more than fitness. Just two and a half hours per week can increase your life by seven whole years.

In the words of Dr. Attia, ‘Exercise is the king of interventions. [It] has a greater impact on your life span and your health span than any of the other [ways to increase life expectancy].’ More than smoking or type two diabetes, for instance.

Of course, it's terribly annoying when the data tells us that hard work beats quick hacks. But such is life.

There are, of course, easier ways to live a long and healthy life. Moving to Sardinia works brilliantly, according to the data. A renowned Blue Zone, where the number of centenarians is unusually high, the data shows a correlation between how steep a village is and how long its inhabitants live. A ten minute walk up the hill to church most days is enough to measurably extend your days. And completely irradiate dementia, as the data seems to say. So many of these Blue Zones have little to no dementia at all. Residents live long, purposeful, active lives and their brains keep up.

So why does all this matter?

Well it turns out that sweatiness, as opposed to cleanliness, is next to godliness. Exercise is everything we need to do to keep the Grim Reaper at bay. Everything else falls into place, post workout.

I hope you enjoyed this foray into the fascinating world of longevity science. Please get in touch if it’s at all interesting to you.

Ben Mason

Independent Marketing Strategist and Co-founder & CEO of Athlete

PS. Longevity is now much more than a hobby to me. Six months ago I launched a startup called Athlete. Life insurance for people who workout. The fitter you are, the less you pay. It felt weird that the very companies who invest in our life expectancy were failing to measure its single biggest indicator. We take the data from your watch or phone and turn it into as much as a 50% discount on your premium. And our longevity coaching app will help you hone your exercise routines, all in the name of more, better years on the clock. Please do get in touch if this floats your boat.

Further reading:

Hi, it's Josh here.

Cast your minds back to 2020, when every Fortune 500 company suddenly discovered racism existed and pledged billions to fix it. Now, in 2025, we're watching those same companies compete to see who can backpedal fastest on their commitments.

So I find myself writing a newsletter I didn't think anyone would have to write in 2025. In defence of DEI.

My sister works for an amazing charity called Team Domenica, helping adults with learning disabilities get into the workplace - meaning I’ve seen up close the incredible impact having a workforce that reflects the community you serve can have. So it’s been particularly disturbing seeing this Trump-triggered ‘sunsetting’ of DEI initiatives across the corporate world.

But while the stampede away from diversity initiatives hits full gallop, here's a quick reminder: ditching DEI isn't just morally bankrupt – it's bad business.

Beyond equal: equity

DEI isn't about giving everyone the same starting line – it's about acknowledging that some runners have been competing with weighted vests. A 2023 study found that Black Americans still face an average $550,000 lifetime earnings gap compared to white peers. For college educated or higher black men, this rises to $1.4M, or 41%. Meanwhile, women still make up only 10% of Fortune 500 CEOs, despite representing over 50% of college graduates. The point isn't to lower the bar; it's to remove the systemic hurdles that keep talented people from reaching it.

It’s the economy, stupid

DEI doesn’t need to be a political issue, but it is a business one. And as luck would have it we already sit on a treasure trove of data that show us diversity is not only a source of power for businesses, but a real competitive advantage.

McKinsey’s latest diversity report found companies in the bottom quartile for executive team diversity are 66% less likely to outperform their rivals financially. More diverse teams report better EBIT margins, and are 70% likelier to capture new markets. The maths isn’t difficult. Diverse teams = more money.

So for those organisations able to row back these initiatives so easily it seems either a) you weren’t measuring the impact, or b) if you were measuring, you weren’t doing DEI right. Pick your poison.

The innovation imperative

We are seeing a huge surge in interest in our innovation capabilities recently, as categories feel crammed with ever diminishing space to play, and consumers aren’t responding to the arms race of incremental features and benefits. Whilst breaking this cycle demands new approaches, processes, and harnessing of new technologies, diversity can also be a secret weapon.

BCG's 2023 data shows companies with above-average diversity produced nearly double the innovation revenue of their peers (45% vs 26% of revenue from new products and services). We know innovation isn't about having the smartest person in the room – it's about having a diverse set of perspectives attacking the problem.

We see this time again. Until 2011, airbags were designed exclusively with male crash test dummies, resulting in women being 47% more likely to suffer serious injuries in car crashes. When Apple finally added female health tracking to the Apple Watch, five years after its launch, the feature generated over 70 million data points in its first nine months – a market hiding in plain sight. These aren't just oversight or mistakes – they're symptoms of a deeper problem that become more critical as the challenges we face grow more complex.

Tomorrow's challenges need today's changes

The challenges facing businesses, and humanity at large aren’t getting easier. They’re bigger, more complex, more interlinked than ever before, and require strategic imagination to decode and find solutions. They’re not going to be solved by rooms full of people who went to the same handful of schools and holiday in the Hamptons.

Early AI systems were great at recognizing pedestrians – as long as they had light skin and weren't using wheelchairs. Why? Because the training data and testing teams lacked diversity. The scientific community increasingly understands the power of diversity, as teams are becoming more diverse in demographics, international scope, and discipline. They seem to grasp what many businesses can’t - the solutions to complex problems won't come from teams that all share the same blind spots.

The biggest breakthroughs aren't coming from homogeneous teams iterating on what worked yesterday. They're coming from diverse groups who see problems differently, who bring different life experiences to the table, who question assumptions that others take for granted. When a team's collective blind spots align with the challenges they're trying to solve, you don't get innovation – you get expensive failures and missed opportunities.

Adapt or die

You can dismantle DEI programs today. But by 2045 $84.4 trillion in wealth will transfer to younger generations, who consistently rank DEI as a top factor in choosing brands and employers. Your competitors aren't just building more diverse companies – they're building companies that will capture the next generation of talent and customers.

It’s not about being perfect, but continuing to invest in broadening the talent pool you draw from, to bring diverse perspectives into the business. Because the data is clear: diverse companies perform better, innovate faster, and attract better talent. Continuing to invest in DEI isn’t just the right thing to do – it’s the smart thing to do.

The question isn't whether diversity matters. The question is whether you'll still be relevant when your customers, employees, and the world have moved on without you.

Josh Hedley-Dent

Senior Director - Client Growth at BeenThereDoneThat

Further reading:

Diversity matters even more: The case for holistic impact

How Diverse Leadership Teams Boost Innovation

Hi, it's Dan here.

How user-led is your organisation?

For the last few years I’ve been lucky enough to work as a trustee with a London charity called Unfold.

Unfold is a mentoring-based charity, helping those who face the most challenges get where they want to be.

I’ve learned huge amounts.

I’ve learned about what brings people to the UK and about what it takes to get up on your feet as an asylum seeker - into our healthcare system, into housing, into schools.

I’ve learned about the power of community and peer support groups.

I’ve learned about how charities work - and the commitment and talent of those who work in this sector.

Most of all though, I’ve learned about listening. Really listening.

Unfold has a fabulous CEO and she has driven a compelling vision for growth, such that we now help ten times more people than three years ago.

This vision is built upon a conviction that Unfold should listen to and be led by the people it serves.

We have therefore established both a Youth Advisory Council (YAC) and a Women’s Advisory Council (WAC) made up of volunteers from among our service users. These groups meet with the Operational team and with the Board multiple times a year. The sessions have been designed to enable feedback from our users on what they see as the most pressing needs for Unfold to address.

And it is now part of the Unfold constitution that both the Operational team and the Board are answerable to the needs of the WAC & the YAC. It’s become a requirement of our governance.

As marketers, we often talk about the importance of remaining anchored off the needs of our audiences - as a path to better product, better communications. And these days AI is enabling us to access these needs at previously unimaginable scale and speed. (BeenThereDoneThat has been working with an expert partner in the AI space on a concept called The Billion Person Focus Group - which tells its own story.)

However what if we, as marketers, radically committed to being user-led?

Not just as a tool for insight, but as a principle for governance.

What would that look like?

It's striking that while countless brands talk about being user-centric, almost none have taken the step of embedding users into their actual governance. In my time on the Dove business under Steve Miles, there were serious conversations about introducing young women into the governance model. But even Dove and the likes of Patagonia who are lauded for their progressive approaches haven't gone this far.

We've seen attempts: Facebook's much-publicized Oversight Board was created to give users a voice in content decisions, but without genuine power to influence platform governance, it became a fig leaf for business as usual. We've become skilled at gathering user feedback, at co-creation, at community engagement. But giving users genuine power? Not so much.

Of course, there are good reasons why. User-led governance is complex. It slows things down. It challenges established power structures. It requires genuine commitment to hearing difficult truths. And it demands that leadership teams are prepared to share control - perhaps the hardest ask of all.

But what if we went further anyway? What if a brand was genuinely accountable to its users - not just through focus groups or customer panels, but through constitutional governance? Where advisory councils had real power to shape direction and strategy. Where users weren't just consulted, but were decision-makers.

It might seem radical. But radical is a powerful point of difference. Just ask the young people and women who are helping shape Unfold's future - if you want to understand someone's needs, start by giving them a seat at the table.

The rest tends to follow.

Dan Gibson

Managing Director at BeenThereDoneThat

Further reading:

For more information on Unfold’s work and how to volunteer as a mentor, please see here.

Hi, it's Melanie here.

I turned 35 last year and, along with it, was unceremoniously dumped into the "35–45" demographic box. As Samantha Jones from Sex and the City might say, “Welcome to my box.” Except, unlike Samantha, I’m not strutting through life in a metallic crop top with cosmopolitans on tap. If anything, my life is more meal planning, failing said meal planning, and spending £600 a month at Tesco on emergency dinners.

But here’s the kicker: when branding agencies and startups dream up their archetypes—“Samantha, 35–45, female, cosmopolitan city-dweller, loves fun, fashion, eating out, and eating in (wink wink)”—it sounds suspiciously like me. Except it’s not. And when the campaigns and products land to market, it’s no surprise that they don’t capture me as a customer. Because (as much as my alter ego would like) I’m not a Samantha.

I’m the 30 something who spends 5–6 nights a week at home, 45 minutes from London’s Soho buzz, with my cat, two kids and a partner. I’m the one meal-prepping for the week (badly), splurging occasionally on a Michelin tasting menu but mostly on sushi takeaway, and tossing Perello olives, elderflower cordial and Tony’s Chocolonely into my Tesco basket to make the mundanity of life feel a bit more deluxe. I’m not one-of-a-kind—there are loads of women like me. But when brands lump us all into a single “demographic,” they lose us entirely.

Demographic Boxes Are Dead. Long Live the Micro-Tribe.

We’ve all heard it: “If you’re speaking to everyone, you’re speaking to no one.” But when it comes to pinpointing their people, brands are still terrified of leaning in. Instead, they cling to the safety of broad, one-size-fits-all demographics. And it’s a big problem.

Here’s the truth: the 35–45 Samantha box might have made sense in the 2000s. Back when media was still mass and Sex and the City was the pinnacle of aspirational marketing. But today? The world is more nuanced. Streaming algorithms serve us niche content. Social media connects us to micro-communities with oddly specific vibes. And as consumers, we expect the same level of intimacy from the brands we buy into.

Think about it: how nice is it when you meet someone and realise you share the same humour, music taste, and lifestyle quirks? You’re not just “35–45” and female. You’re someone who bonds over Schitt’s Creek quotes, avoids small talk, and actually loves a tacky family resort in Lake Garda for the mix of kid chaos and Aperol spritzes. That level of connection feels magical. So why is it so hard for brands to replicate?

The Fear Factor

I think it boils down to fear. Brands are scared that if they narrow their focus, they’ll alienate potential customers. But here’s the irony: by trying to speak to everyone, they alienate everyone.

It’s the equivalent of showing up to a party and saying, “I love… music! And food! And Netflix!” Cool. We all do. But what if you said, “I’m obsessed with mid-2000s emo bands, garlic bread, and The Great British Bake Off.” Suddenly, you’ve got people (albeit not the entire room) nodding along, ready to bond. The same goes for branding.

The brands that succeed today are the ones that aren’t afraid to alienate the wrong people to deeply connect with the right ones. Look at Glossier, who built a cult following by speaking to millennial women with skinimalist aspirations. Or Liquid Death, who turned water into a lifestyle brand for edgy, punk rock enthusiasts. Neither tries to appeal to the masses, but both have built wildly loyal audiences.

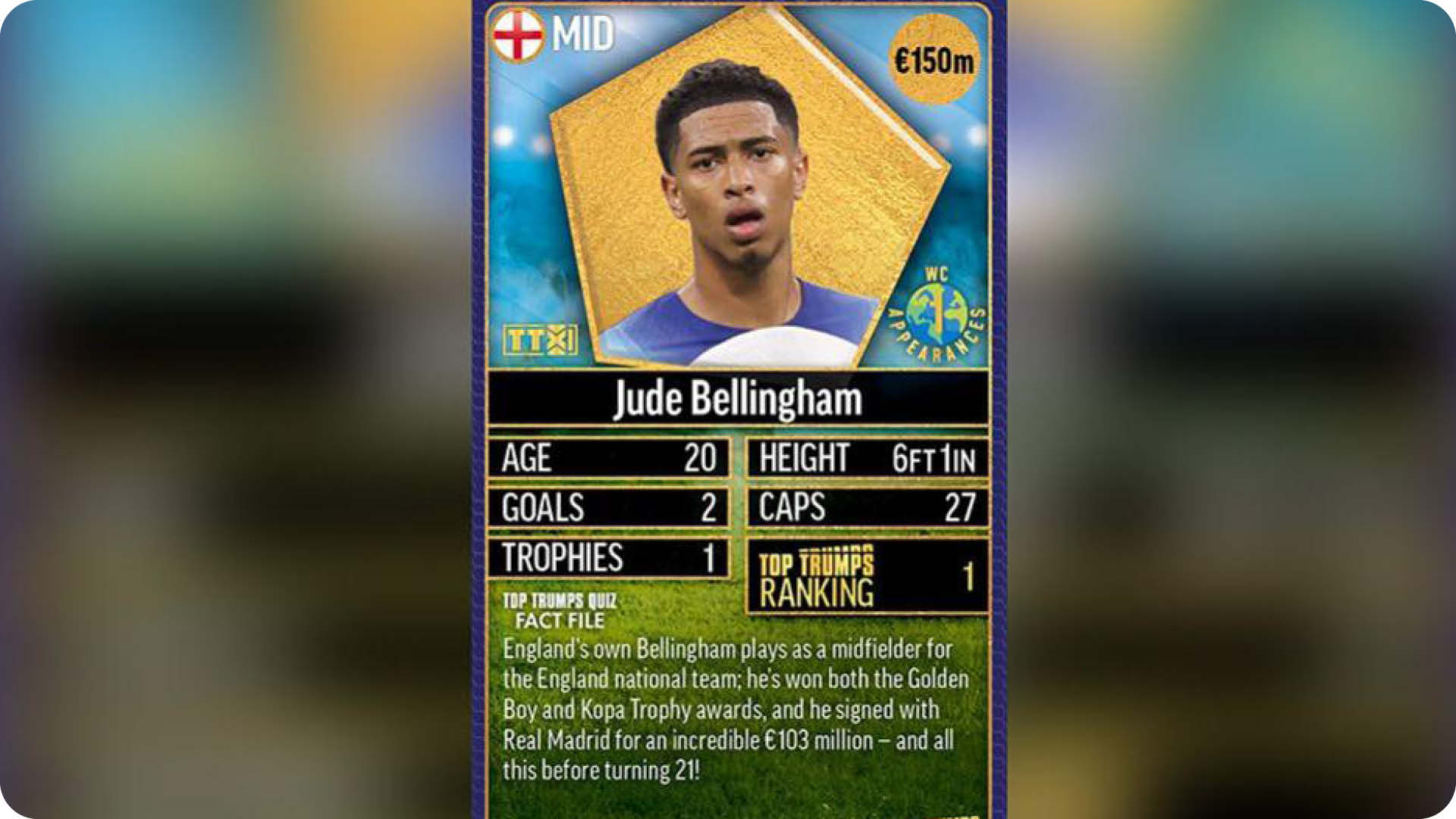

Enter: The Top Trumps of Branding

This brings me to my solution: the Top Trumps of branding.

Bear with me. About eight years ago, a good friend made me a personalised deck of Top Trumps cards. Each card ranked my family and friends on arbitrary traits—humour, karaoke talent, emotional availability. It was equal parts hilarious and horrifying to see your entire social circle ripped apart by a divisive ranking system.

But it got me thinking: what if brands treated their audiences like a pack of Top Trumps? Instead of lumping us into broad brackets, they could rank micro-communities by hyper-specific traits and build campaigns accordingly.

For example, instead of “Samantha, 35–45,” you get:

- Humour: Dry wit, thrives on sarcasm.

- Lifestyle: Primarily a routined homebody with moments of glamour + adventure

- Spending habits: Sensible, impulsive moments of ‘pick me ups’ + fundamental uppers to my life

- Brand kryptonite: Makes my life easier, makes my life more exciting

Building Brands for Humans, Not Brackets

The truth is, most of us aren’t looking for brands that understand our age bracket or income level. We’re looking for brands that get us. Brands that feel like they’re part of our crew—whether that crew is bonding over Real Housewives, the new Middle Eastern spot for a date night, or the unapologetic joy of staying in on a Friday night looking at my fig tree.

So here’s my challenge to marketers: stop speaking “demographic.” Start speaking human. Use the tools at your disposal—data, analytics, cultural nuance—to build micro-tribes, not mass audiences. And don’t just speak to these tribes—celebrate them, quirks and all.

Because if a campaign doesn’t make your audience feel like they’ve just met their new best friend? It’s already failed.

Let’s trade the tick boxes for Top Trumps and build brands that don’t just sell—but connect. After all, isn’t that what we’re all really here for?

Melanie Goldsmith

Co-Founder of Juicy Brick

Further reading:

Sentimental in the City 1 Podcast: Sex & The City, Season One

Eugene Healey on how people don’t always ‘identify’ with brands: and sometimes that’s for the best.

The X Factor makes me feel old

Hi, it's Jacob here.

There’s one trend I’ve been talking about more than any other with clients over the last two years. It’s a truly huge shift that affects nearly everything. And it isn’t AI. It’s neatly encapsulated by this chart that John Burn-Murdoch recently published in the FT:

As you can see from the charts, people over 40 spent roughly the same amount of time alone in 2023 as they did in 2010, in US, UK and Europe. The elderly spend more time alone than other age groups.

But the big shift is that 20-year-olds in the US and UK now spend 2 more hours alone per day than they did in 2010. And that your average 20-year-old now spends as much time alone as a 60-year-old. This is not a minor change in behaviour, like choosing yoga over pilates. Humans are a social species and we all go a little mad when we’re alone too much, as 2020-21 amply demonstrated.

A lot has been written about the impact of so much time alone on big societal issues like mental health, civic engagement and political polarisation. But for the stick-rattling community there are some more concrete and immediate implications that it’s interesting to think about.

People who don’t socialise much have far less incentive to drive. So young people’s increasing aversion to social contact might have a lot to do with the precipitous decline in driving among the under 30s:

Similarly, the rise in alcohol abstinence among the young is well-documented. The pat explanation is the rise in “wellness culture”. This probably displays a lot of marketing’s class bias, as can be seen by the pricing and marketing of alcohol substitutes on both sides of the Atlantic.

But a recent study that asked teenagers to self-report on why alcohol was drunk less by young people flags a second, almost as large effect: changing patterns of socialisation:

My cynical side says this effect may be even bigger than the research suggests. Concern about alcohol-related harm is the socially acceptable reason to give for not drinking. It’s rather more embarrassing to state that the reason you don’t drink is that you’ve got no one to do it with.

The same study also pulls out the popularity of weed as a substitute for alcohol. What it doesn’t mention, but I believe is extremely relevant, is that cannabis users worldwide report that the way they enjoy the drug is for physical pleasure rather than social lubrication. In other words cannabis is a better drug for solo consumption than alcohol.

Much has been made of the impact of online dating on how easy it is to find a potential partner. But it’s interesting to note that, despite the undoubted convenience of these services, they don’t really seem to be working:

What if the decline in birth rates and marriages across the world isn’t just because of people prioritising careers or concerns about money, could it be a clear consequence of simply socialising less? It’s hard to meet a partner if you just don’t meet anyone…

Matt Klein published a fascinating breakdown of Pornhub statistics. The one that jumps out for me is that “hentai” (animated porn) went from the 10th most searched term in the US in 2014 to the most searched term in 2024, with Gen Z users 193% more likely than average to view hentai porn in 2024. Maybe, for some, getting together with an actual human seems so unlikely, it's not even a fantasy anymore?

Another clear consequence is in eating habits. Research by OpenTable indicates a 14% rise in Brits dining alone, with young people particularly likely to do so: 79% of millennials and Gen Z indicated they plan to dine alone in the next year. Restaurants will need to adapt to this by adjusting the balance of table sizes they offer, as well as the types of dishes - fewer sharing platters and more single portion dishes is the obvious consequence. Indeed 50% of solo diners in the OpenTable research indicated they’d had difficulty getting a booking for one.

The standard scapegoat for all of this is social media. However the degree of social isolation is on a linear upward trajectory, whereas time on social media (and indeed time spent on all media) has virtually plateaued.

Burn-Murdoch’s data concurs. The big shift is less in spending a lot more time on social media, and more in doing alone what used to be done together. Primarily watching television as can be seen from American Time Use data from 2024:

I suspect there’s a second-order effect here. It’s not that people are doomscrolling instead of going out. It may be more likely that spending more time alone saps people’s confidence about going out, and causes them to lose the habit, so that they then spend more time alone.

I’ll leave the hand-wringing to other writers. For marketers there are some obvious winners and losers in terms of categories: there are clear challenges for alcohol, nightlife and fashion. There is a clear upside for gaming, streaming video, snacking, ecommerce and delivery food.

An unexpected but fundamental shift might be in social media itself. There’s been a decade-long decline in engagement with “traditional” social platforms that centre around “sharing” content from “friends”. The hit platforms of today are based around user preferences and content recommendation algorithms rather than social ties. This will only accelerate as genuine content is swamped out by AI slop.

In many ways the story of the last 20 years in marketing has been the declining relevance of constructed brand promotions in favour of organic spread - the classic “viral product” story. But as social ties are weakened and disrupted, this may become less prevalent. We’re certainly likely to see the continued rise of influencers as a channel - where social ties are declining, parasocial ones are rising. But perhaps we will also see that advertising begins to rise in importance again as the primary source of social cues about the “meaning” of products in people’s lives.

(disclaimer: the author has worked in advertising for most of his life)

Jacob Wright

Problem Definer & Marketing Consultant

Hi, it's Anna here.

I genuinely love making New Year's resolutions, and always follow through on those I set. But this year is different, I’m moving around too much to form habits or see clearly the path I’m on. So instead of goals, I'm working on a 2025 manifesto. More vibes and intentions than goals and ticklists. After two decades in advertising, it’s a familiar format for me.

Manifestos have been used for centuries by academics, artists, politicians and provocators to challenge conventions, spark debates and explore the irrational. The Communist Manifesto might be the most notable example. Widely referenced, though too dense to be widely read.

Centuries after Marx and Engles outlined a worker’s revolution, the manifesto is once again a trending Google search. There has been much speculation over Luigi Mangione's scrawled note and at the time of writing journalists are still unpacking why a Tesla Cybertruck was blown up in front of Trump Tower.

Despite these darker appropriations, manifestos continue to evolve as tools for radical imagination. While the Futurists once proclaimed the death of museums, more contemporary artist manifestos often explore the spaces between the self and the system. The Cyberfeminist Manifesto is one of my favourites, drawing a through line from the womb (“matrix” in Latin) to the internet matrix: “we are… saboteurs of big daddy mainframe.”

These creative proclamations often embrace contradiction rather than certainty, suggesting that perhaps the most radical act is to remain open to continuous transformation. Less destroying the old world and more imagining multiple possible futures simultaneously.

I wonder if this resurgence of manifestos will influence how we think of the form in advertising.

Thanks to agencies like Wieden+Kennedy, manifestos have been spilling out of pitch decks and onto our screens for years. Our commercial breaks are filled with booming voices declaring things like "where there are cooks there is hope" to sell butter. The most compelling brand manifestos succeed by doing what art manifestos have always done - they make the familiar strange again.

Diverging from Marx the advertising industry has developed a particular style of creative manifesto. Short sentences. Punchy sentiments. Fragmented like the way we consume media.

But, some brands use the creative format to express deeper corporate commitments. When Patagonia declared "Don't Buy This Jacket," they demonstrated how the sum of a manifesto can be bigger than the short sentences it contains. Their message carried weight because it emerged from decades of environmental activism - inviting us to reimagine our relationship with consumption.

Nike's "Just Do It" touches something deeper about human potential and Apple's "Think Different" simultaneously critiques and participates in corporate culture. Their impact comes from this intersection of style and substance rather than choosing between the two.

The most famous brand manifestos work at this meta-level, not just selling products but reframing how we think about entire categories of experience. They give us handholds on massive cultural shifts, creating what philosopher Timothy Morton might call a "hyperobject" - something too large to see in its entirety but that we can feel the edges of.

As we move deeper into an era where brands increasingly function as cultural actors, the role of brand manifestos becomes more complex. What happens when corporate declarations become our most widely-shared visions of possible futures? How do we navigate the space between authentic cultural contribution and commodified revolution? These are questions worth exploring as we continue to blur the lines between commerce, culture, and collective imagination.

As we step into 2025, an age where attention spans shrink but crises loom larger, perhaps the manifesto - brief, bold, uncompromising - is exactly the form we need. Or perhaps, brands should leave this form to the artists and the assassins and move on to something new?

Anna Rose Kerr

Freelance Creative Director & Consultant

Further reading:

A compendium of brand manifestos

The Cyberfeminist Manifesto (NSFW)

A beginners guide to the Communist Manifesto

You could try clearing the filters, using different filters or the search box.

What got you here

won't get you there...

So Where Next?

Join Our Newsletter